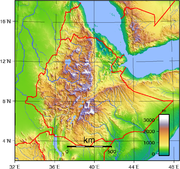

Geography of Ethiopia

Ethiopia is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered on the north and northeast by Eritrea, on the east by Djibouti and Somalia, on the south by Kenya, and on the west and southwest by Sudan. The country has a high central plateau that varies from 1,290 to 3,000 m (4,232 to 9,843 ft) above sea level, with the highest mountain reaching 4,533 m (14,872 ft). Elevation is generally highest just before the point of descent to the Great Rift Valley, which splits the plateau diagonally. A number of rivers cross the plateau—notably the Blue Nile rising from Lake Tana. The plateau gradually slopes to the lowlands of the Sudan on the west and the Somali-inhabited plains to the southeast.

Contents |

Physical features

Topography

Between the valley of the Upper Nile and Ethiopia's border with Eritrea is a region of elevated plateaus from which rise the various tablelands and mountains that constitute the Ethiopian Highlands. On nearly every side, the walls of the plateaus rise abruptly from the plains, constituting outer mountain chains. The highlands are thus a clearly marked orographic division. In Eritrea, the eastern wall of this plateau runs parallel to the Red Sea from Ras Kasar (18° N) to Annesley Bay (also known as the Bay of Zula) (15° N). It then turns due south into Ethiopia and follows closely the line of 40° E for some 600 km (373 mi). About 9° N there is a break in the wall, through which the Awash River flows eastward. The main range at this point trends southwest, while south of the Awash Valley, which is some 1,000 m (3,281 ft) below the level of the mountains, another massif rises in a direct line south. This second range sends a chain (the Ahmar mountains) eastward toward the Gulf of Aden. The two chief eastern ranges maintain a parallel course south by west, with a broad upland valley in between — in which valley are a series of lakes — to about 3° N, the outer (eastern) spurs of the plateau still keeping along the line of 40° E. The southern escarpment of the plateau is highly irregular, but has a general direction northwest and southeast from 6° N to 3° N. It overlooks the depression in which is Lake Turkana and — east of that lake — the southern Debub Omo Zone (part of the larger Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region). The western wall of the plateau from 6° N to 11° N is well marked and precipitous. North of 11° N the hills turn more to the east and fall more gradually to the East Sudanian savanna plains at their base. On its northern face the plateau falls in terraces to the level of the eastern Sudan. The eastern escarpment is the best defined of these outer ranges. It has a mean height of 2,100 to 2,400 m (6,890 to 7,874 ft), and in many places rises almost perpendicularly from the plain. Narrow and deep clefts, through which descend mountain torrents that lose themselves in the sandy soil of the Eritrean coast, afford means of reaching the plateau, or the easier route through the Awash Valley may be chosen. On surmounting this rocky barrier, the traveller finds that the encircling rampart rises little above the normal level of the plateau.

The physical aspect of the highlands is impressive. The northern portion, lying mainly between 10° and 15° N, consists of a huge mass of Archaean rocks with a mean height of 2,000 to 2,200 m (6,562 to 7,218 ft) above sea level, and is flooded in a deep central depression by the waters of Lake Tana. Above the plateau rise several irregular and generally ill-defined mountain ranges which attain altitudes of from 3,700 m (12,139 ft) to just under 4,600 m (15,092 ft). Many of the mountains are of unusual shape. Characteristic of the country are the enormous fissures which divide it, formed over time by the erosive action of water. They are in fact the valleys of the rivers which, rising on the uplands or mountain sides, have cut their way to the surrounding lowlands. Some of the valleys are of considerable width; in other cases the opposite walls of the gorges are but two or three hundred meters apart, and fall almost vertically thousands of meters, representing an erosion of many hundred thousands cubic metres of hard rock. One result of the action of the water has been the formation of numerous isolated flat-topped hills or small plateaus, known as ambas, with nearly perpendicular sides. The highest peaks are found in the Semien and Bale ranges. The Semien Mountains lie northeast of Lake Tana and culminate in the snow-covered peak of Ras Dejen, which has an altitude of 4,550 m (14,928 ft). A few kilometers east and north respectively of Ras Dejen are Mounts Biuat and Abba Yared, whose summits are less than 100 meters (328 ft) below that of Ras Dejen. The Bale Mountains are separated from the larger part of the Ethiopian highlands by the Great Rift Valley, one of the longest and most profound chasms in Ethiopia. The highest peaks of that range include Tullu Demtu, the second-highest mountain in Ethiopia (4,377 m/14,360 ft), Batu (4,307 m/14,131 ft), Chilalo (4,036 m/13,241 ft) and Mount Kaka (3,820 m/12,533 ft).

Parallel with the eastern escarpment are the heights of Biala, 3,810 m (12,500 ft), Mount Abuna Yosef, 4,190 m (13,747 ft), and Kollo, 4,300 m (14,108 ft), the last-named being southwest of Magdala. Between Lake Tana and the eastern hills are Mounts Guna, 4,210 m (13,812 ft), and Uara Sahia, 3,960 m (12,992 ft). In the Choqa Mountains of Misraq Gojjam, Mount Choqa (also known as Mount Birhan) attains a height of 4,154 m (13,629 ft). Below 10° N, the southern portion of the highlands has more open tableland than the northern portion and fewer lofty peaks. Though there are a few heights between 3,000 and 4,000 m (9,843 and 13,123 ft), the majority do not exceed 2,400 m (7,874 ft), but the general character of the southern regions is the same as in the north: a much-broken hilly plateau.

East of the highlands towards the Red Sea there is a strip of lowland semi-desert, the Ethiopian xeric grasslands and shrublands.

Hydrology

Most of the Ethiopian uplands have a decided slope to the north-west, so that nearly all the large rivers flow in that direction to the Nile, comprising some 85% of its water. Such are the Tekezé River in the north, the Abay in the center, and the Sobat in the south, and about four-fifths of the entire drainage is discharged through these three arteries. The rest is carried off by the Awash, which runs out in the saline lacustrine district along the border with Djibouti; by the Shebelle River and the Jubba, which flow southeast through Somalia, though the Shebelle fails to reach the Indian Ocean; and by the Omo, the main feeder of the closed basin of Lake Turkana.

The Tekezé River, which is the true upper course of the Atbarah River, has its headwaters in the central tableland; and falls from about 2,100 to 750 m (6,890 to 2,461 ft). in the tremendous crevasse through which it sweeps west, north, forming part of the border with Eritrea, and west again down to the western terraces, where it passes from Ethiopia to Sudan. During the rains the Tekezé (i.e. the "Terrible") rises some 5 m (16.4 ft) above its normal level, and at this time forms an impassable barrier between the northern and central regions. In its lower course, the river is known by the Arabic name Setit. In Sudan, the Setit is joined (at ) by the Atbarah, a river formed by several streams which rise in the mountains west and northwest of Lake Tana. The Gash or Mareb, which forms part of the border with Eritrea, is the most northerly of the highland rivers which flow toward the Nile valley. Its headwaters rise on the landward side of the eastern escarpment within 80 km of Annesley Bay on the Red Sea. It reaches the Sudanese plains near Kassala, beyond which place its waters are dissipated in the sandy soil. The Mareb is dry for a great part of the year, but like the Takazze is subject to sudden freshets during the rainy season. Only the left bank of the upper course of the river is in Ethiopian territory.

The Abay — that is, the upper course of the Blue Nile — has its source near Mount Denguiza in the Choqa mountains (about ), and first flows for 110 km (68.4 mi) nearly due north to the south shore of Lake Tana. Tana, which stands 750 to 1,000 m (2,461 to 3,281 ft) below the normal level of the plateau, has somewhat the physical aspect of a flooded crater. It has an area of about 2,800 square kilometres (1,081 sq mi), and a depth in some parts of 75 m (246 ft). At the southeast corner the rim of the crater is, as it were, breached by a deep crevasse through which the Abay escapes, and here makes a great semicircular bend like that of the Tekezé, but in the reverse direction — east, south and north-west — down to the plains of Sennar, where it takes the name of Bahr-el-Azrak or Blue Nile. The Abay has many tributaries. Of these, the Bashilo rises near Magdala and drains eastern Amhara; the Jamma rises near Ankober and drains northern Shoa; the Muger rises near Addis Ababa and drains south-western Shoa; the Didessa, the largest of the Abay's affluents, rises in the Kaffa hills and has a generally south-to-north course; the Dabus runs near the western edge of the plateau escarpment. All these are perennial rivers. The right-hand tributaries, rising mostly on the western sides of the plateau, have steep slopes and are generally torrential in character. The Belassa, however, is perennial, and the Rahad and Dinder are important rivers in flood-time.

In the mountains and plateaus of Gambela and Kaffa in southwestern Ethiopia rise the Baro, Gelo, Akobo and other chief affluents of the Sobat tributary of the Nile. The Akobo, in about , joins the Pibor, which in about unites with the Baro, the river below the confluence taking the name of Sobat. These rivers descend from the mountains in great falls, and like the other Ethiopian streams are unnavigable in their upper courses. The Baro on reaching the plain becomes, however, a navigable stream affording an open waterway to the Nile. The Baro, Pibor and Akobo form for 400 km (249 mi) the western and southwestern frontiers of Ethiopia.

The chief river of Ethiopia flowing east is the Awash River (or Awasi), which rises in the Shewan uplands and makes a semicircular bend first southeast and then northeast. It reaches the Afar Depression through a broad breach in the eastern escarpment of the plateau, beyond which it is joined on its left bank by its chief affluent, the Germama (Kasam), and then trends round in the direction of the Gulf of Tadjoura. Here the Awash is a copious stream nearly 60 m (197 ft) wide and 1.2 m (3.94 ft) deep, even in the dry season, and during the floods rising 15 to 20 m (49 to 66 ft) above low-water mark, thus inundating the plains for many kilometers along both its banks. Yet it fails to reach the coast, and after a winding course of about 800 km (497 mi), it passes (in its lower reaches) through a series of badds (lagoons) to Lake Abhe Bad (or Abhe Bid) on the border with Djibouti and some 100 to 110 km (62 to 68 mi) from the head of the Gulf of Tadjoura. In this lake the river is lost. This remarkable phenomenon is explained by the position of Abhe Bad in the centre of a saline lacustrine depression several hundred meters below sea level. While most of the other lagoons are highly saline, with thick incrustations of salt round their margins, Abhe Bad remains fresh throughout the year, owing to the great body of water discharged into it by the Awash.

Another lacustrine region extends from the Shoan heights southwest to the Samburu (Lake Turkana) depression. In this chain of scenic upland lakes — some fresh, some brackish, some completely closed, others connected by short channels — the chief links in their order from north to south are: Zway, communicating southwards with Hara and Lamina, all in the Arsi Zone; then Abijatta with an outlet to a smaller turn to the Baroda and Gamo areas, skirted on the west sides by grassy slopes and wooded ranges from 2,000 m (6,562 ft) to nearly 3,000 m (9,843 ft) high; lastly, Lake Chew Bahir (formerly known as Lake Stephanie) which is completely closed and falling to a level of about 550 m (1,804 ft) above sea level. To the same system obviously belongs the neighbouring Lake Turkana, which is larger than all the rest put together. This lake receives at its northern end the waters of the Omo, which rises in the Shoan highlands and is a perennial river with many affluents. In its course of some 600 km (373 mi) it has a total fall of about 2,000 m (6,562 ft), from 2,500 m (8,202 ft) at its source to c. 500 m (1,640 ft) at lake level), and is consequently a very rapid stream, being broken by the Kokobi and other falls, and navigable only for a short distance above its mouth. The chief rivers of Somalia, the Webi Shebelle and the Jubba, have their rise on the south-eastern slopes of the Ethiopian escarpment, and part of their course is through territory belonging to Ethiopia.

There are numerous hot springs in Ethiopia, such as Sodere.

Seismology

Earthquakes are common in Ethiopia.

Geology

The East African tableland is continued into Ethiopia. A pioneering study of the geology of Ethiopia was W. T. Blanford's work in 1870. More recent work has focussed on the Afar Depression, due to its importance as one of two places on Earth where a mid-ocean ridge can be studied on land (the other is Iceland).

The following formations are represented:

- Sedimentary and metamorphic

-

- Recent: Coral, alluvium, sand

- Tertiary: Limestones of Harrar

- Jurassic: Antalo Limestones

- Triassic: Adigrat Sandstones

- Archaean: Gneisses, schists, slaty rocks

Archaean.--The metamorphic rocks compose the main mass of the tableland, and are exposed in every deep valley in Tigre and along the valley of the Blue Nile. Mica schists form the prevalent rocks. Hornblende schist also occur and a compact felspathic rock in the Suris defile. The foliae of the schists strike north and south.

Triassic.--In the region of Adigrat the metamorphic rocks are invariably overlain by white and brown sandstones, unfossiliferous, and attaining a maximum thickness of 300 m. They are overlain by the fossiliferous limestones of the Antalo group. Around Chelga and Adigrat coal-bearing beds occur, which Blanford suggests may be of the same age as the coal-bearing strata of India. The Adigrat Sandstone possibly represents some portion of the Karroo formation of South Africa.

Jurassic.--The fossiliferous limestones of Antalo are generally horizontal, but are in places much disturbed when interstratified with trap rocks. The fossils are all characteristic Oolite forms and include species of Hemicidaris, Pholadomya, Ceromya, Trigonia and Alaria.

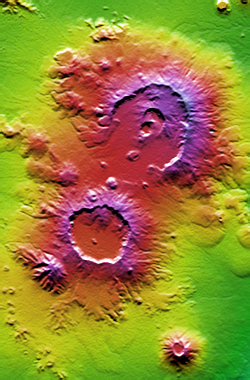

Igneous Rocks.--Above a height of 2,400 m (8,000 ft) the country consists of bedded traps belonging to two distinct and unconformable groups. The lower (Ashangi group) consists of basalts and dolerites often amygdaloidal. Their relation to the Antalo limestones is uncertain, but Blanford considers them to be not later in age than the Oolite. The upper (Magdala group) contains much trachytic rock of considerable thickness, lying perfectly horizontally, and giving rise to a series of terraced ridges characteristic of central Ethiopia. They are interbedded with unfossiliferous sandstones and shales. Of more recent date (probably Tertiary) are some igneous rocks, rich in alkalis, occurring in certain localities in southern Ethiopia. Of still more recent date are the basalts and ashes west of Massawa and around Annesley Bay and known as the Aden Volcanic Series. With regard to the older igneous rocks, the enormous amount they have suffered from denudation is a prominent feature. They have been worn into deep and narrow ravines, sometimes to a depth of 1,000 to 1,200 m (3,000 to 4,000 ft).

Climate

See also: Climate

The climate is temperate on the plateau and hot in the lowlands. At Addis Ababa, which ranges from 2,200 to 2,600 m (7,218 to 8,530 ft), maximum temperature is 26 °C (78.8 °F) and minimum 4 °C (39.2 °F). The weather is usually sunny and dry, but the short (belg) rains occur from February to April and the big (meher) rains from mid-June to mid-September. The climate of Ethiopia and its dependent territories varies greatly. The Somali Region and the Danakil lowlands in the Afar Region have a hot, dry climate producing semi-desert conditions; the country in the lower basin of the Sobat is hot, swampy and malarious. But over the greater part of Ethiopia as well as the Oromia highlands the climate is very healthy and temperate. The country lies wholly within the tropics, but its nearness to the equator is counterbalanced by the elevation of the land. In the deep valleys of the Tekezé and Abay, and generally in places below 1,200 m (3,937 ft), the conditions are tropical and diseases such as malaria are prevalent. On the uplands, however, the air is cool and bracing in summer, and in winter very bleak. The mean range of temperature is between 15 to 25 °C (59 to 77 °F). On the higher mountains the climate is Alpine in character. The atmosphere on the plateaus is exceedingly clear, so that objects are easily recognizable at great distances. In addition to the variation in climate dependent on elevation, the year may be divided into three seasons. Winter, or the cold season, lasts from October to February, and is followed by a dry hot period, which about the middle of June gives place to the rainy season. The rain is heaviest in the Tekezé basin in July and August.

In the former provinces of Gojjam and Welega heavy rains continue till the middle of September, and occasionally October is a wet month. There are also spring and winter rains; indeed rain often falls in every month of the year. But the rainy season proper, caused by the southwest monsoon, lasts from June to mid-September, and commencing in the north moves southward. In the region of the headwaters of the Sobat the rains begin earlier and last longer. The rainfall varies from about 750 mm (29.5 in) a year in Tigray and Amhara to over 1,000 mm (39.4 in) in parts of Oromia. The rainy season is of great importance not only to Ethiopia but to the countries of the Nile valley, as the prosperity of the eastern Sudan and Egypt is largely dependent upon the rainfall. A season of light rain may be sufficient for the needs of Ethiopia, but there is little surplus water to find its way to the Nile; and a shortness of rain means a low Nile, as practically all the flood water of that river is derived from the Ethiopian tributaries.

Flora and fauna

As in a day's journey the traveller may pass from tropical to almost Alpine conditions of climate, so great also is the range of the flora and fauna. In the valleys and lowlands the vegetation is dense, but the general appearance of the plateaus is of a comparatively bare country with trees and bushes thinly scattered over it. The glens and ravines on the hillside are often thickly wooded, and offer a delightful contrast to the open downs.

These conditions are particularly characteristic of the northern regions; in the south the vegetation on the uplands is more luxuriant. Among the many varieties of trees and plants found are the date palm, mimosa, wild olive, giant sycamores, junipers and laurels, the myrrh and other gum trees (gnarled and stunted, these flourish most on the eastern foothills), a magnificent pine (the Natal yellow pine, which resists the attacks of the white ant), the fig, orange, lime, pomegranate, peach, apricot, banana, and other fruit trees; the grape vine (rare), blackberry, and raspberry; the cotton and indigo Plants, and occasionally the sugar cane. There are in the south large forests of valuable timber trees; and the coffee plant is indigenous in the Kaffa country, whence it takes its name. Many kinds of grasses and flowers abound. Large areas are covered by the kosso, a hardy member of the rose family, which grows from 2.5 to 3 m (8.2 to 9.8 ft) high and has abundant pendent red blossoms. The flowers and the leaves of this plant are highly prized for medicinal purposes. The fruit of the hurarina, a tree found almost exclusively in Shoa, yields a black grain highly esteemed as a spice. On the tableland a great variety of cereals and vegetables are cultivated. A fibrous plant, known as the sansevieria, grows in a wild state in the semi-desert regions of the north and south-east.

In addition to the domestic animals enumerated below the fauna is very varied. Elephant can be found in certain low-lying districts, especially in the Sobat valley. The hippopotamus and crocodile inhabit the larger rivers flowing west, but are not found in the Hawash, in which, however, otters of large size are plentiful. Lions abound in the low countries and in Somaliland. In central Ethiopia the lion is no longer found except occasionally in the river valleys. Leopards, both spotted and black, are numerous and often of great size; hyenas are found everywhere and are hardy and fierce; the lynx, wolf, wild dog and jackal are also common. Boars and badgers are more rarely seen. The giraffe is found in the western districts, the zebra and wild ass frequent the lower plateaus and the rocky hills of the north. There are large herds of buffalo and antelope, and gazelles of many varieties and in great numbers are met with in most parts of the country. Among the varieties are the greater and lesser kudu (both rather rare); the duiker, gemsbuck, hartebeest, gerenuk (the most common—it has long thin legs and a camel-like neck); klipspringer, found on the high plateaus as well as in the lower districts; and the dik-dik, the smallest of the antelopes, its weight rarely exceeding 5 kg (11 lb), common in the low countries and the foothills. The civet is found in many parts of Ethiopia, but chiefly in the Galla regions. Squirrels and hares are numerous, as are several kinds of monkeys, notably the guereza, gelada, guenon and dog-faced baboon. They range from the tropical lowlands to heights of 3,000 m (9,843 ft).

Birds are very numerous, and many of them remarkable for the beauty of their plumage. Great numbers of eagles, vultures, hawks, bustards and other birds of prey are met with; and partridges, duck, teal, guineafowl, sandgrouse, curlews, woodcock, snipe, pigeons, thrushes and swallows are very plentiful. A fine variety of ostrich is commonly found. Among the birds prized for their plumage are the marabout, crane, heron, blacks bird, parrot, jay and hummingbirds of extraordinary brilliance,

Among insects the most numerous and useful is the bee, honey everywhere constituting an important part of the food of the inhabitants. Of an opposite class is the locust. There are thousands of varieties of butterflies and other insects. Snakes are not numerous, but several species are poisonous.

Natural resources and land use

Ethiopia has small reserves of gold, platinum, copper, potash, and natural gas.[1] It has extensive hydropower potential.[1]

Of the total land area, about 20 percent is under cultivation, although the amount of potentially arable land is larger.[1] Only about 10 to 15 percent of the land area is presently covered by forest as a result of rapid deforestation during the last 30 years.[1] Of the remainder, a large portion is used as pasturage. Some land is too rugged, dry, or infertile for agriculture or any other use.[1]

Environmental issues

Disputed territory

The border between Ethiopia and Eritrea has never been precisely demarcated.[1] Between 1998 and 2000, the two countries fought a war over the issue, which involves quite small enclaves along the northern segment of their border, including the tiny village of Badme and the enclave of the Irob people.[1] In 2002 an international boundary commission delimited the border.[1] Although both nations agreed to accept its decision, Ethiopia has refused to accept the commission’s findings in full, much to the consternation of the Eritrean government.[1] The central section of Ethiopia’s border with Somalia also has never been fully demarcated and is only provisional.[1] Questions remain about the precise location of small parcels along the border with Sudan as well.[1]

Statistics

- Location

- Eastern Africa, west of Somalia

- Geographic coordinates

- Map references

- Africa

- Area

-

- Total: 1,127,127 km²

- Land: 1,119,683 km²

- Water: 7,444 km²

- Land boundaries

- Coastline

- 0 km (landlocked)

- Maritime claims

- None (landlocked)

- Climate

- Tropical monsoon with wide topographic-induced variation

- Terrain

- High plateau with central mountain range divided by Great Rift Valley

- Elevation extremes

-

- Lowest point: Danakil, -125 m

- Highest point: Ras Dejen, 4,533 m

- Natural resources

- Small reserves of gold, platinum, copper, potash, natural gas, hydropower

- Land use

-

- Arable land: 12%

- Permanent crops: 1%

- Permanent pastures: 40%

- Forests and woodland: 25%

- Other: 22% (1993 est.)

- Irrigated land

- 1,900 km² (1993 est.)

- Natural hazards

- Geologically active Great Rift Valley susceptible to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions; frequent droughts

- Environment - current issues

- Deforestation; overgrazing; soil erosion; desertification

- Environment - international agreements

-

- Party to: Biodiversity, Climate Change, Desertification, Endangered Species, Ozone Layer Protection

- Signed, but not ratified: Environmental Modification, Law of the Sea, Nuclear Test Ban

- Geography - note

- Landlocked - entire coastline along the Red Sea was lost with the de jure independence of Eritrea on 24 May 1993

See also

- Ethiopia

- Extreme points of Ethiopia

- List of lakes in Ethiopia

- List of mountains in Ethiopia

- List of rivers of Ethiopia

- List of volcanoes in Ethiopia

- Ilemi Triangle

- Mandera triangle

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the CIA World Factbook.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the CIA World Factbook.

External links

- Maps of Ethiopia - Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin

- The soil maps of Ethiopia, EuDASM

- Ethiopia entry at The World Factbook

- The mapping of Ethiopia Ethiopia-United States Mapping Mission web site

- ETHIOPIA TOPOGRAPHIC MAPS East View Cartographic web site

- Ethiopia's government mapping agency, Ethiopian Mapping Authority web site

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||